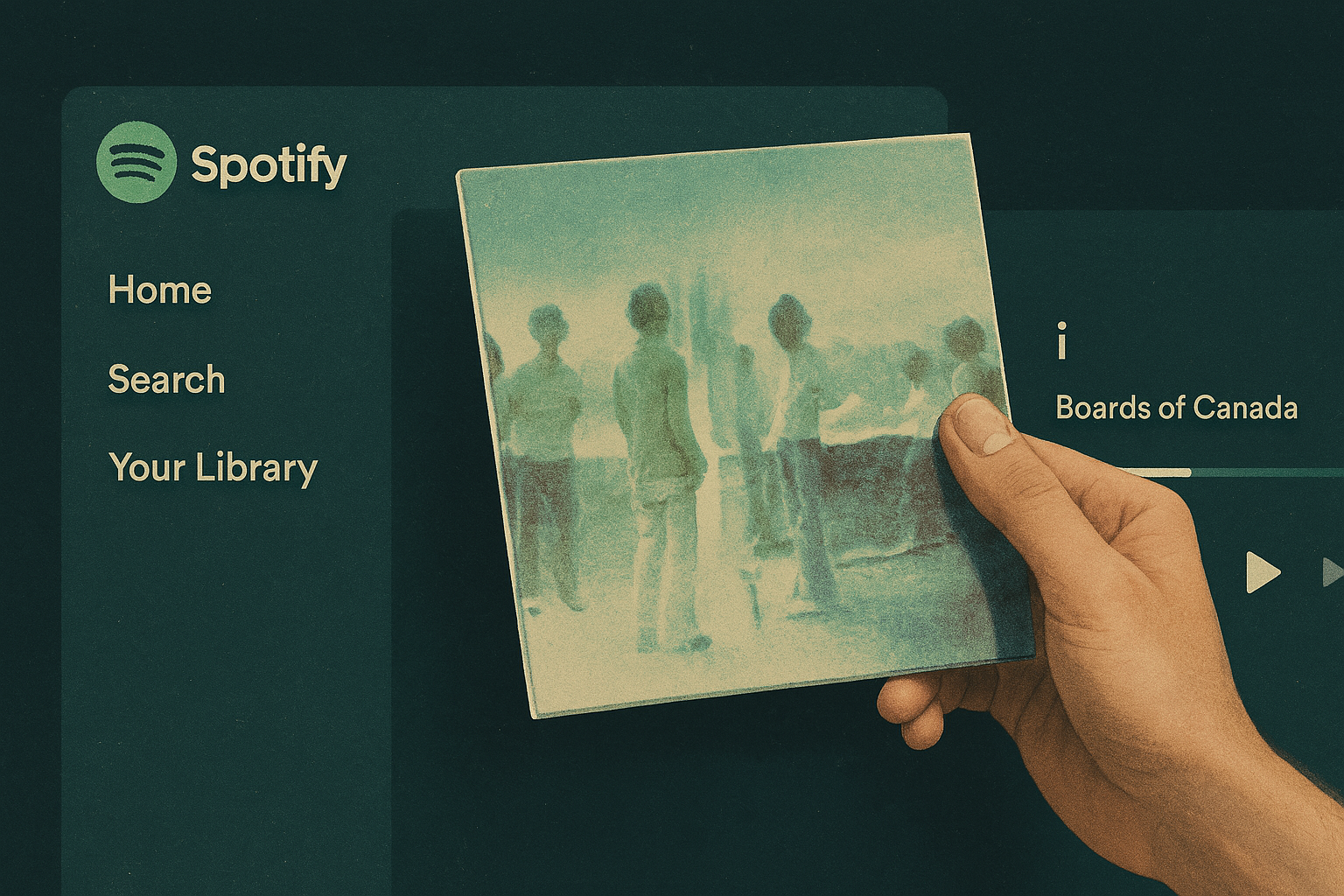

What have we lost while music got easier to play? We hit play every day, but do we ever really listen? Spotify, MP3s, algorithms, and the value that slipped away.

ASCOLTARE DAVVERO – CHAPTER 1

Is Spotify the problem? Or just a mirror?

There’s a gesture we’ve come to take for granted over the past twenty years: pressing “play.” On a phone, a computer, a speaker. Music starts, follows us, distracts us, comforts us. But rarely does it stop us.

And yet, not so long ago, listening meant something else. It meant picking a record. Entering a store. Waiting for a release. Listening meant making time. An active, almost ritual act. Today, more often, it simply means not being in silence.

This is not about nostalgia. Or snobbery. It’s about asking ourselves: what did we lose while everything got easier? And above all: is it still possible to reclaim our way of listening without rejecting the present?

In this series of articles, we’ll reflect together on what happened to the way we listen. We’ll talk about how our relationship with music changed; what artists like Prince and David Bowie foresaw long ago; why vinyl’s return, though fascinating, isn’t a real solution; and how we might still learn to use digital platforms in a more conscious and human way.

But first, we need to understand when the change began. And for that, we have to go back to a German lab, where a group of engineers decided that an entire album could fit into a few megabytes.

When music lost weight: the MP3 file

In late ’80s Germany, the Fraunhofer Institute developed an audio compression system that would change the world. The MP3 was born: revolutionary, compact, practical, smart.

How does it work? It uses a principle called psychoacoustic compression, based on how the human ear perceives sound. Our cochlea, the spiral-shaped part of the inner ear, sends electrical signals to the brain which “translates” them into sound. But not all frequencies are perceived equally: some cover others, and certain details go unnoticed.

The MP3 codec exploits these perceptual limitations to eliminate what “isn’t really heard.” The result? A file ten times smaller. A masterpiece of engineering. But also, in a way, a photocopy of music. Perfect—yes—but only until you compare it to the original.

From file to flow: then came streaming

With MP3s, music became digital, dematerialized. Then came Napster, then eMule, then iPods, and everything else. The physical record gave way to the file, and the file, soon after, to the stream.

Spotify didn’t invent the problem. Spotify refined it.

- It gives you access to everything, anytime

- It suggests what to listen to

- It knows you better than you think

It’s convenient, sure. But also dangerously fluid. Listening becomes passive, constant, frictionless. You scroll, listen, forget.

Is Spotify guilty? Or just the result of a demand?

Spotify solved many problems:

- It reduced piracy

- It allowed millions to discover new music

- It democratized access

But it created new ones:

- It devalued the worth of each single listen

- It fragmented attention

- It turned artists into content providers

Maybe the issue isn’t the platform itself. Maybe it’s that we stopped asking questions.

“Do we still truly listen, or are we just filling the silence?”

So now what? We can still choose.

The point isn’t to demonize technology. It’s to become present again in the act of listening.

- Don’t quit Spotify — use it with intention

- Don’t chase perfect sound — seek meaningful experience

- Don’t count streams — remember what stays with you

In the next chapter, we’ll talk about those who already understood all this. Visionary artists who saw where we were heading — and tried, in their own way, to stop time.

Next chapter: Prince, Bowie and the unheard prophecy

Stay tuned.

Our project is independent and non-profit.

If you enjoy what we do, you can support us with a small donation.

This article was produced with the support of AI tools, used for content organization and textual optimization. The sources, ideas and materials come from the archive and activity of the Dancity Association.